Wartime Mobilization in Late Colonial Korea: Enforcing Everyday Use of the ‘National Language,’ 1937-1945

This presentation is derived from my second book project exploring the imperial subjectification (hwangminhwa or kōminka) policies in late colonial Korea (1937-1945) and Korean responses to them. The book challenges the conventional view that imperial subjectification policies were radical assimilation processes that sought to eliminate the Korean ethnic identity. Rather than being absorbed into the Japanese identity, the colonized Koreans engaged in a series of complex negotiations and engagements with the demands of wartime mobilization, including what we might call “bargaining strategies,” to reconfigure the meaning of being a “Korean” in the Japanese empire. It examines various features of the imperial subjectification policies, including enforcement of Shinto shrine worship, implementation of volunteer soldier program and eventually conscription of all eligible Koreans, infiltration of the everyday lives of the colonized Koreans by ideologies and practices of imperial patriotism and the notorious “surname change” program that sought to integrate Korean and Japanese family systems.

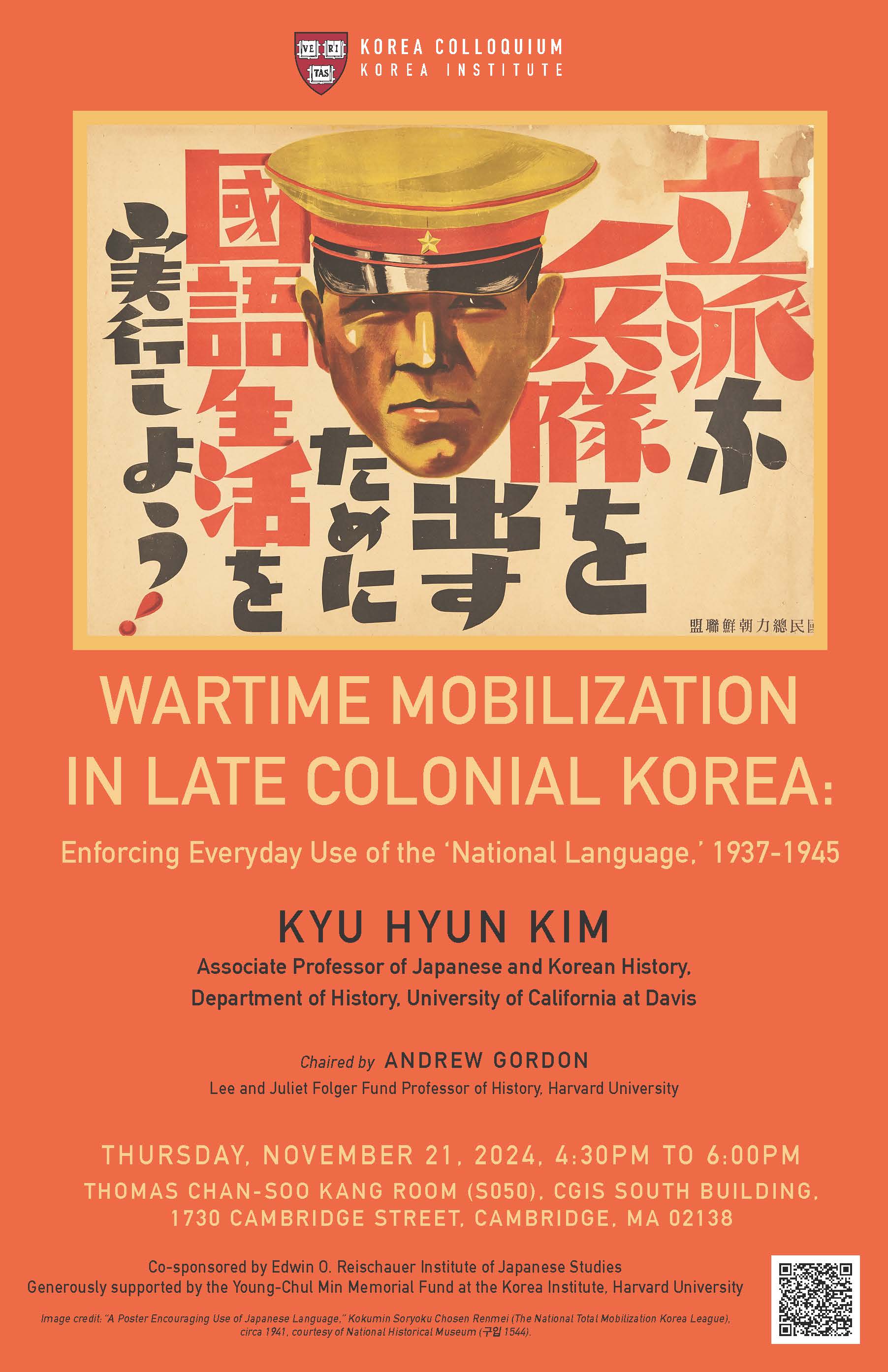

This presentation will focus on one of the wartime mobilization policies, the drive for everyday use of “national language” (kugŏ sangyong or kokugo jōyō) in late 1930s and early 1940s. Unlike the conventional view of this drive, it was never designed to “abolish” Korean language. Infiltration of the local, everyday and private realms of the lifeworld of the colonized Koreans by the colonizer’s language generated complex and variegated responses from them, some Koreans taking advantage of educational opportunities provided by this initiative in order to obtain social mobility. Moreover, despite the obvious hegemonic position assigned to the Japanese language, linguistic conditions of colonial Korea remained bilingual or even hybrid. In the end, the colonial regime could neither make the “national language,” i.e. Japanese, into an everyday language of the lifeworld of the colonized, nor establish it as a shared language of a multiethnic empire, in other words, something other than an “ethnic language” of the Japanese people. As we can see in the case of the persecution of the Korean Language Association (Chosŏnŏ Hakhoe) in 1942, the Japanese colonial regime’s failure in fact reinforced, rather than weakened, the status of Korean language as a signifier of Korean ethnic identity.

***

To attend this event online, please register here.

Generously supported by the Young-Chul Min Memorial Fund at the Korea Institute, Harvard University

Korea Colloquium co-sponsored by the Reischauer Institute.